This month, I would like to share a thought or two on an important topic: making sure that a disabled person’s wishes are the main, central focus on anything that has an impact on their well-being and life experience, even if they are young and low-speaking. As someone who relies on others to transition through all the things NT’s [neurotypicals] take for granted, it could be the difference between having someone support me appropriately and respectfully and that person creating a narrative about me which excludes my voice.

This month, I would like to share a thought or two on an important topic: making sure that a disabled person’s wishes are the main, central focus on anything that has an impact on their well-being and life experience, even if they are young and low-speaking. As someone who relies on others to transition through all the things NT’s [neurotypicals] take for granted, it could be the difference between having someone support me appropriately and respectfully and that person creating a narrative about me which excludes my voice.

For example, when I was little, I was forced to take part in forty hours of therapy every week. There were some great people who played with me and stayed in our lives up to now, but there were a few who gave me a view of themselves that my family didn’t see until much later.

Like the person who told the team that she was afraid I was going to hurt her when I was stressed. I used to seek out the pressure point that results when you touch foreheads with another person. I found it immediately calming and connecting with another person, and all of the people who worked with me knew this and accepted it. Except for this one person. For whatever reason, this action made her uncomfortable, and so she pathologized it. Had she shared why it made her uncomfortable, I believe there would have been a good discussion around it that would have benefited everyone; instead, she alienated herself by pathologizing a ten-year old. Lucky for me, the rest of the team knew the reason I did it and could teach me ways to be gentle while I was anxious.

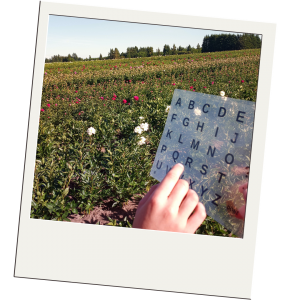

Another example is one that could have had life-changing implications for me had it been the primary discourse available. When I was twelve, I was still getting hours of therapy every week, but it was at this office space where there were other children. I had started using a letterboard, and was practicing on it every day for up to a half hour with my mom. She asked the staff to consider trying it with me too, but they wouldn’t, stating that it wasn’t research-based. So things at the program stayed exactly the same, while at home my head was being filled with all sorts of lessons on art, history, and science.

It came to a point where my mother had reached out to the school district about me returning to general education, so they sent two people to observe me to determine whether I could be in a general classroom. They came to see me at the ABA [applied behavior analysis] program where the staff was working on letter recognition worksheets which, of course, was terribly embarrassing because I was frustrated to have such a baby display of my skills. Imagine their reaction when they came to my house a week later and observed me answering questions about the Lusitania on my letterboard.

I overheard one of the observers say “Damn,” and he got up and walked once around the table. It seemed like he was looking to see what the trick was, how I was communicating so well at home while in this setting that was supposed to be the gold standard was so lacking in presuming my competence. At my IEP, these two school officials were my biggest cheerleaders. Imagine what could have been the outcome had they chosen the assessment of the ABA program over the lesson conducted with a “researchless” form of assistive technology? I owe them both my diploma and my poetry because I would have never discovered anything more advanced than Dr. Seuss in the self-contained classroom which was the only alternative setting offered.

I overheard one of the observers say “Damn,” and he got up and walked once around the table. It seemed like he was looking to see what the trick was, how I was communicating so well at home while in this setting that was supposed to be the gold standard was so lacking in presuming my competence. At my IEP, these two school officials were my biggest cheerleaders. Imagine what could have been the outcome had they chosen the assessment of the ABA program over the lesson conducted with a “researchless” form of assistive technology? I owe them both my diploma and my poetry because I would have never discovered anything more advanced than Dr. Seuss in the self-contained classroom which was the only alternative setting offered.

Now that I can communicate with others through my letterboard, I see there are so many missed opportunities for giving the perspective of people like me, and I hope more of you make room for more of us in decisions that affect our lives.